There is always a jolt when you realise that your career can be measured in decades. Imagine then when I did the necessary subtraction to find that it was four and a tenth decades since my first excavation – Winchester Unit 1976 by the way, nice and sunny, didn’t realise then that most digs were cold, wet and muddy.

I thought I’d celebrate this milestone – 41 years and still managing to hang on as a freelance lithic specialist – with something I’ve never done before…

I had never written the word ‘Stonehenge’.

There we go, I’ve done it now Stonehenge, Stonehenge, Stonehenge. Many of you will find this peculiar: if you are not an archaeologist then you most probably think that I would naturally know all about it along with Pyramids and Romans. If you are an archaeologist then you might think it amazing that I have managed my entire career without hanging on to its coat-tails.

Well, a goodly portion of prehistoric archaeology is done in the UK without reference to Stonehenge and despite the massive amount of attention paid to Stonehenge in the press and academia it is in reality a construct of Archaeology in the South of England. I even managed to get through an MA in Prehistory and Archaeology at Sheffield in the early 80s without much reference to Stonehenge – it was all Oppida, Oronsay and oh yes, the Romans.

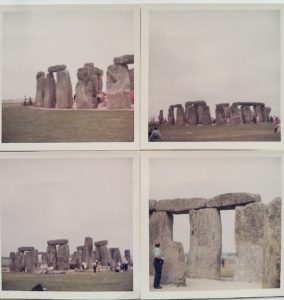

But I was looking through family snaps the other day and found these four blurry photographs taken with Mum’s Kodak Instamatic, probably around the late 60s. I won’t say that this family visit turned me on to archaeology, in fact I most likely spent the time playing with a boomerang off camera or fighting with my brothers. The photographs themselves tick quite a few trendy boxes: the ‘Stonehenge’ box; the ‘Vintage’ box; the ‘Hipster real film’ box; the ‘Family holiday memory’ box. But I am struck by how much change these images show.

See how long ago people wandered around the stones, apparently undirected, unstructured, uninformed by the State. How some of the stones were the perfect height for resting weary legs, or scrambling on. With the distance of time – half a century – this disregard for the wear and tear of the monument will seem shocking to some folk. Others will look at the photographs and see how the stones themselves seem to wrap around and shepherd the people wandering amongst them and yearn for that simpler time when the monument was not guarded so closely.

Whatever your viewpoint, the last 50 years have made their own history at Stonehenge and left new postholes, paths, and roads encircling the monument; there is vegetation regrowth, backfilled excavation trenches and signage for future archaeologist to investigate. These researchers might observe an apparent retreat from the stones with no major interaction after the mid 1970s. Maybe geophysics will record that a new monument was built nearby that appeared to collect and funnel people at some distance around the earlier monument.

How will the future interpret this period of the late 20th/early 21st Century AD? Perhaps they will call it the cult of look but don’t touch; that we revered our past through keeping it at distance.

I wonder what the next fifty years will bring in the life of Stonehenge and whose histories it will be part of. It is a pretty close bet though that my first mention of Stonehenge is also likely to be my last.