Tweeting suits me. Write a short message, rip it off the notepad and throw it out there. And repeat. Some messages drop straight to the ground. Others flap around before landing. Occasionally they get taken up in a gust and are blown every which way before disappearing.

I took to Twitter @annclarkerocks to promote my work over a year ago. As a freelance archaeologist you only have yourself to bring in the work. Over the years I’ve developed a website, sent out advertising postcards to Commercial Units across the UK, dabbled with LinkedIn – too corporate, and Facebook – just a confusing guddle of information. The regular promotional platform, the conference, has always been difficult for me in the past – cost, access, the childcare issue, not having anything zippy to say, as well as sitting quietly in a darkened room for hours listening to frequent uninspiring talks all combine to make this a networking nightmare for me, and many other people! Whether I’ve attracted any extra work as a result of the self-promotion is a moot point but like all archaeology businesses we need to get our name out there and hopefully to people who want work from us.

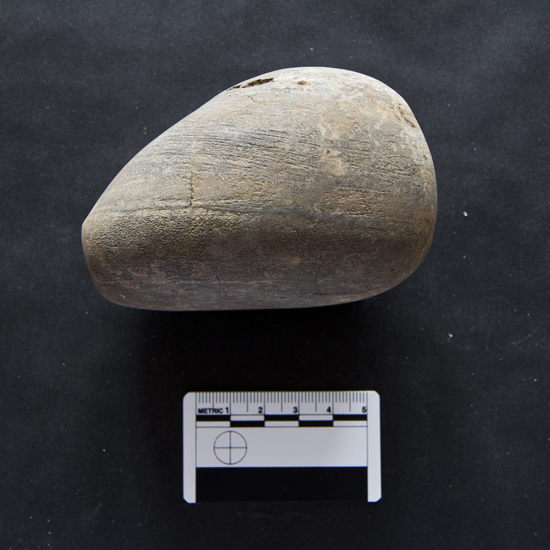

I particularly love using Twitter as a platform to share images of the fabulous range of stone tools that I work on. As well as flaked lithics of all materials and ages, I research stone tools which are much more diverse in form, and use, than flaked tools. Have a look through my Twitter feed – you will be amazed at all the ways stone was shaped into tools in the past.

I’m glad that many folk have liked and commented on these images over the last year. Many of you will have been introduced to particular tool forms for the very first time and I consider that a job well done. It’s good to share.

But what interests me most is how the Twitter audience likes, and engages with, the familiar. I call this the Axe Factor. A quick look through the statistics of my feed shows that of the 100 odd tweets about stone tools of all sorts, the most liked and engaged with were the six images of ground stone axeheads – and the two polissoirs. Other favourites were also ground stone tool forms such as the spatulate tools and ground stone knives – both axehead look-alikes.

Why this strong engagement with the familiar? And what makes axeheads so familiar in the first place? I would consider several of the tool forms I have tweeted about to be of greater importance to the study of the past than stone axeheads: the ground stone from the Mesolithic structure Cass ny Hawin 2, Isle of Man; the huge assemblage of Mesolithic worked ochre from Stainton West, Cumbria; and the Bronze Age ‘handled clubs’ from Shetland, to name but a few. But these are not in the public imagination because the Axe Factor is a direct result of showing off our past as bling; promoting those objects perceived to be most powerful and authoritative; often the most photogenic; and through this maintaining the fiction of archaeology as ‘treasure’.

This came back to bite us very recently during the recent Cadbury debacle. In this case Twitter was the perfect platform to express the collective dismay of archaeologists. But how did we get it so wrong to start with that a large company felt able to promote our heritage in this damaging way? Despite all our professed public engagement will we ever be able to tweak the public perception of archaeology from Treasure Hunting to engaging with and taking an informed interest in our shared past.

And can we really use social media to promote new knowledge?

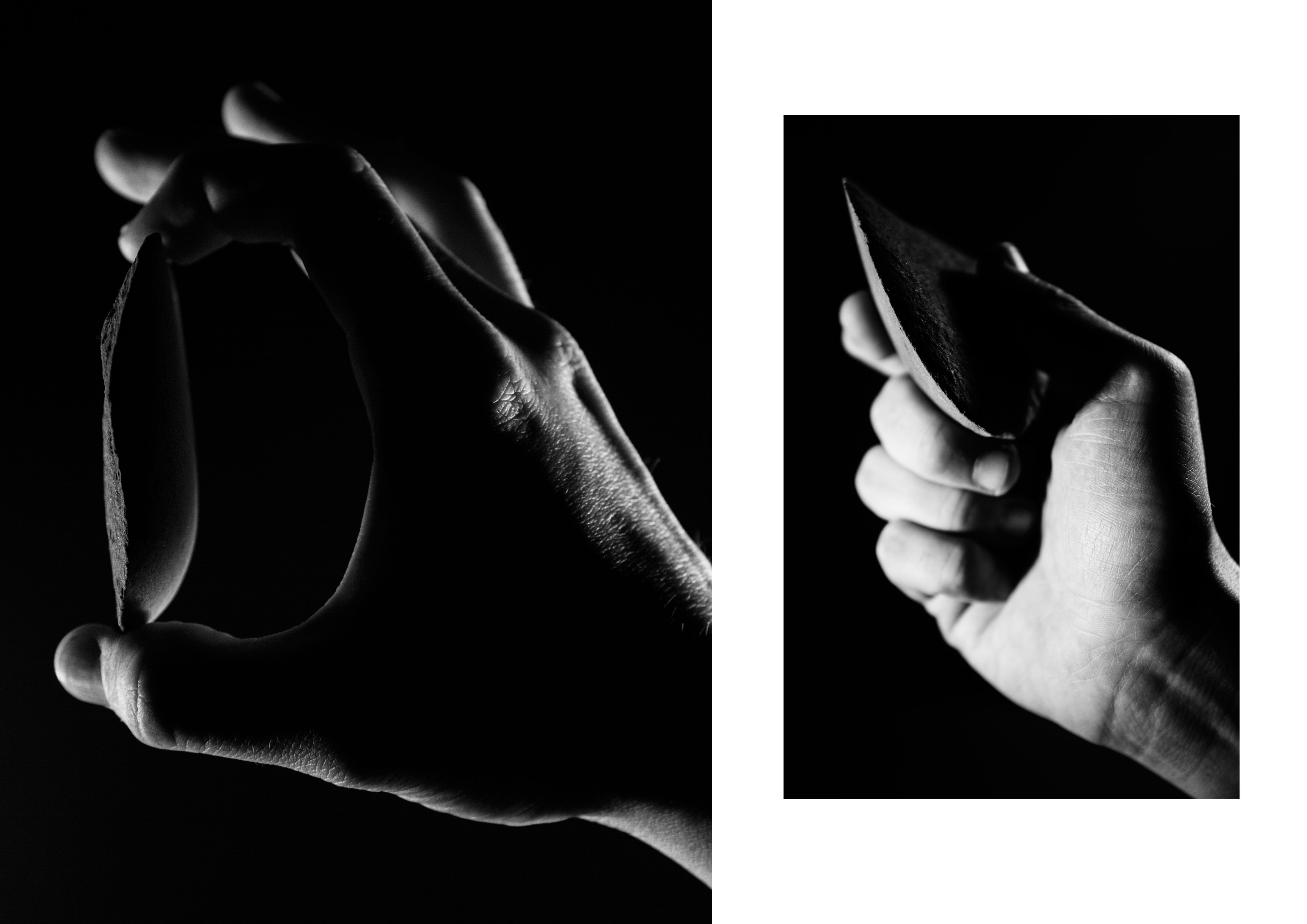

I leave you with a mighty image by Woody Musgrove of a simple sandstone flake from Neolithic Orkney. Is this bling? You decide.